Pego: Chasing Water

A hidden oasis in the increasingly desertified South of Portugal.

The trees bear the colours of autumn—shades of copper, ochre and bronze. Except it isn't autumn. These trees are dying from a lack of water, due to the persistent drought that has engulfed the south of Portugal over the past few years. The more time spent this region, the more it becomes apparent that without water—rain more specifically, there is no life to speak of. Surely an obvious point when considered in factual terms, particularly for someone who studied environmental science at college—yet, to know something conceptually is very different to a deeper level of knowing, the kind that only lived-experience can provide.

These days, I feel more frequently drawn to fresh water. That is, drawn to the relatively scarce sources of fresh water that still remain during the drought. There aren't many such places, but I've often been someone who values quality over quantity anyway. A true oasis in what appears to be an increasingly desertified land, Pego das Pias is one of the last relatively untouched natural treasures of the south-west Alentejo region. Indeed, at this time of year it seems to be the only place suited to really escape the heat. Defined by a valley with a small river that flows during winter and spring, the barranco runs deep—with enough depth to jump from the rocky granite cliffs and plunge into the cold waters below.

Those who know the area will be aware that the dirt track to Pego has two viable options: the first is usually the one that most tourists take, having been directed by their phone navigation to what is usually a death trap for normal cars. This way is littered with potholes and ditches. I once saw a tourist driving his new Porsche on this road, stopping every few metres to remove every stone and pebble in his path. It seemed rather pointless to me, especially since the entire chassis was probably scraped to pieces already. An appropriate form of punishment for relying too heavily on navigation technology, I would say. Never trust it with full certainty. Confie em você, meu amigo. The other option is the more discreet path, often only known by the locals. It follows the opposite side of the river, offering a relatively smooth journey for a dirt track. It requires a short walk to the pools, apparently something that is considered highly unacceptable to the comfort-loving tourists. The irony is palpable.

I pull up at my usual parking spot, underneath a tall birch tree. The leaves sway and dance in the breeze, waving an invitation towards the fresh water that it depends upon. Lupa is always enthusiastic to disembark, jumping from the passenger seat to immediately mark his territory. The herd of goats can usually be heard before they are seen, with the bells ringing softly as they graze on the dry grass—a peaceful symphony that rings through the entire valley. The walk takes us deeper into the forest, away from the eucalyptus plantations that continue to spread through the area like an infection, the symptom of chronic industrial hunger. As we walk further, the natural biodiversity begins to reappear. Even the air has a different quality to it, somehow smoother and easier to breathe. No longer engulfed in clouds of dust or under attack by the summer sun, the hostility of the world behind us is almost forgotten. Calma.

Apart from the usual groups of nude hippies sitting in circles, either camping in tents or in their old vans, Pego das Pias is relatively calm and undisturbed today. During the summer season, one can only pray that there aren't as many tourists as there usually is. Perhaps they were dissuaded by the Google maps reviews that complained about the "poor conditioned road". Fine by me. As is often the case, new visitors usually don't make it past the first pool—a circular basin with a giant boulder in the middle. Whether due to simply not knowing or being avert to exertion, this fact makes me feel rather content.

The trail continues to lead up and around the first pool, narrowing as it passes along the edge of the water. Around the corner are the weird and wonderful rock formations of the barranco. Many thousands of years of erosion eventually create a jagged ridge, with a very deep pool below it. No one knows how deep this water is exactly, although the perceived blackness of its colour would infer that it is pretty damn deep. At the highest point, probably around ten or eleven metres, the adrenaline-seeking cliff divers will throw themselves overboard and plunge into the darkness below.

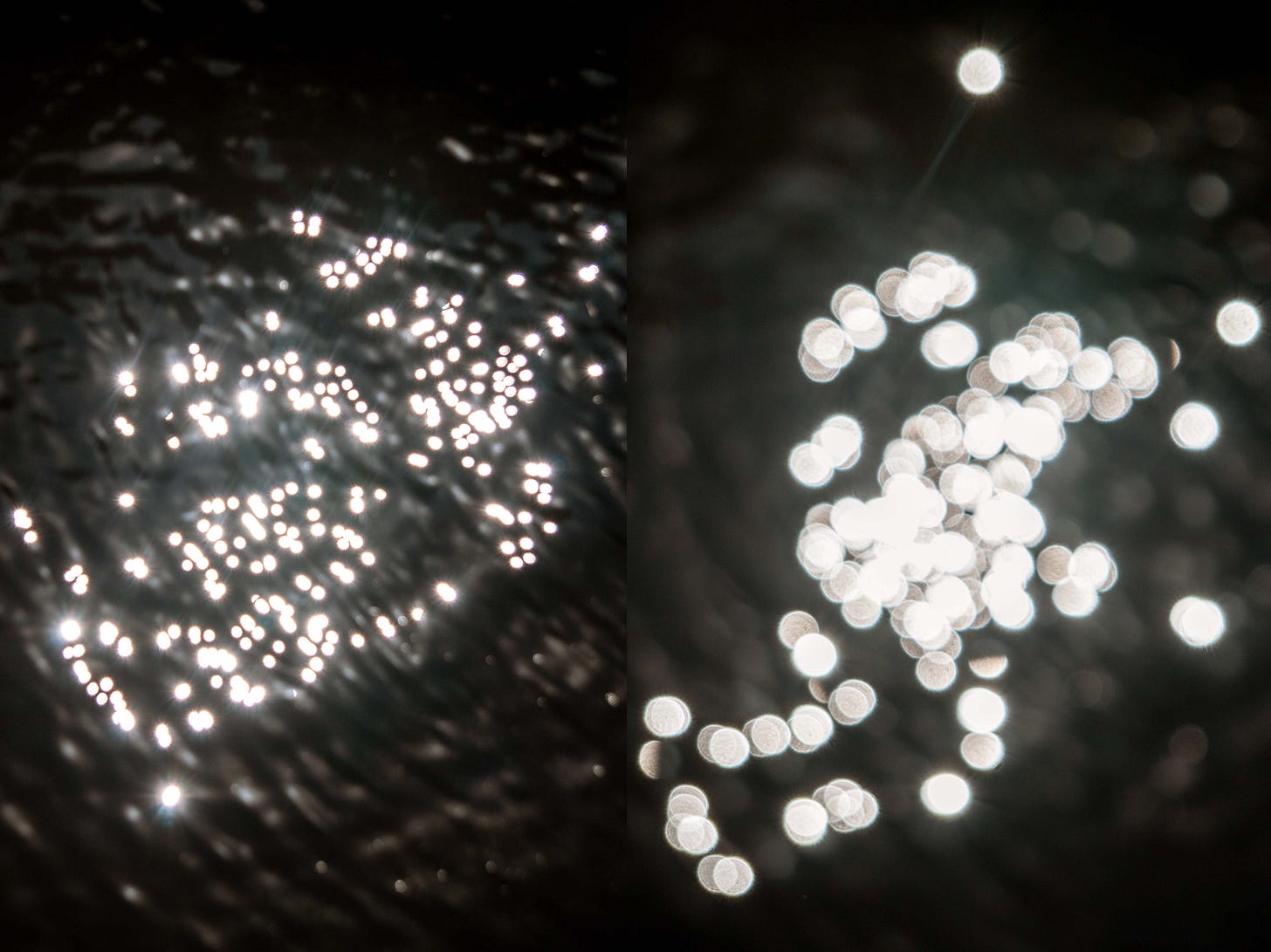

Personally, I'm content with taking the middle height plunge. I step towards the edge of the rock, struck with the same hesitation that gets me every time I take the leap. I step backwards, knowing that procrastination will only amplify the nerves. I take a few steps, before leaping into a cannonball formation. Time becomes increasingly abstract in these few moments between take off and landing—neither here nor there. Not on land or in water. The space between impact feels freeing, yet for a moment it is also simultaneously fear-inducing. This is the edge, the space that those who are drawn to extremes will speak of—the experience of being truly alive. I hit the water and sink to the depths, my feet lightly touching the vegetation at the bottom. I float upwards gently, allowing buoyancy to do the work, then breach the surface of the water—feeling a sense of clarity that is always derived from swimming in cold water. My senses are acutely sharpened. In this hyperaware state, I notice subtle details that I might normally miss—the reflections of light and water on the rocks above, moving with effortless fluidity, like a projector displaying an abstract work of art. The vines swinging from the trees, moving gently in the breeze.

Swimming further down into the crevasse, the water becomes increasingly darker and colder, changing with the depths. There is a certain eeriness to the feeling of floating in a body of water which you can’t see through. It is an experience which I would imagine to be similar to floating through space—a vast emptiness, o vazio. A sensation of being completely supported, yet simultaneously vulnerable and exposed. I head back towards the safety of land, the terrestrial world. Climbing up the side of the rock wall, each movement careful and deliberate—a natural way reveals itself for the perfect placement of hands and feet. After the contrast of cold water, the warmth of the afternoon sun is a welcoming presence. I walk back to the edge of the rock, the place where I leapt into the ravine, into the unknown. Making myself comfortable on the warm granite surface, I sit and observe the dance of light and water once again. Intuitive and effortless, I am restored to a primal way of being. Always within us but often forgotten. Far removed from the constrictions and stresses of the techno-industrial world, life is at once simple and innately satisfying. A return to simplicity. The gift of the water.

A wonderfully descriptive piece of writing as usual. I don't like to visualise you cannonballing off that ledge into the abyss below though!

You have such a beautiful way with words. I almost feel like I'm there experiencing things in real time, that's magic. This makes me even more excited for my future move. I, too hope to discover hidden treasures in the future!