Carved Lands

Starting anew in the Swiss Alps and filming with a local craftsman in an unlikely place.

“Would you like to go up the mountain first?” Roger asks.

I answer yes, without hesitation.

The morning light is stretching slowly across the Albula Alps, turning shadowed slate into illuminated shards of amber and gold. Gravel crunches beneath the small tires of Roger’s nimble Suzuki.

The air is dry and cold, far colder than feels appropriate for late August. But we are above two thousand metres now, and I’m reminded of it as we stare out in awe across this Alpine amphitheatre animated by rock, forest, and light.

“Do you ever get bored of this view?” I ask, aware of my own growing familiarity and fading sense of wonder since I arrived here only a few weeks ago.

“In a way you get used to it, but it still makes me smile.” He responds, his deep voice seeming one with the mountain itself, a mountain man in every sense.

At the beginning of August, I arrived in the Swiss Alps.

It was a necessary migration of sorts — I ran out of funds and couldn’t continue as before. The details aren’t important or relevant to this story, but it seems an important footnote as to why I’m suddenly two thousand kilometers away from where I was prior.

The last month has been strange. I watched a mountain range I had grown so familiar with burn to ashes.

I spoke to friends who were fighting the fire, desperately keeping it away from the villages where it was rapidly encroaching. It was a debilitating thing to witness, knowing that there was little I could do to help.

I needed to divert my focus into what I can be doing now, something useful, something productive — this frustratingly familiar period of limbo when starting over again in a new place — when I came across a story about a local farmer-turned-knife-maker who lives in the upper Engadin region of the Swiss Alps.

It was the spark of inspiration I needed, so I reached out and received a response a few days later.

“Good day. Thank you for your email and your interest in my work. I would be delighted to work with you for a day. (My English isn't that good, but I hope it works out anyway.) Kind regards, Roger”

For a moment I have to remember that I am not looking at a green screen, that this is real and tangible. Otherworldly, yet very much of this world.

We clamber back into the silver Suzuki, and Rogers accelerates vigorously over the gravel tracks. As the day would progress, I realise the way he drives is very much reflective of his way of being.

“This car was made for these gravel roads, wasn’t it?” I ask.

Roger chuckles with his low-pitched, Germanic tone and answers, “Yes, for sure, and you can do this…” as he pulls the handbrake into the corner before his house, sending the back end of the car skirting out diagonally, kicking up dust and rock.

A builder working on the neighbouring house stands with his mouth part-open, speechless. I can already tell we are going to get along well.

We’re standing in an open-air barn, stacked with farming and blacksmith tools. Organised chaos, I believe it’s called.

The smelting furnace is fired up. Small flames shoot out of a gap in the door.

This creative cave is in the lower part of the farmhouse, built in a typically Alpine style: huge in structure, built to accommodate both humans and animals, and built out of wood from the evergreen forests that surround these glacial valleys.

As Roger begins his process, so do I begin mine. It is a strange sort of dance — flitting around this space from one end to another, swapping and interchanging various tools.

It’s a strange sort of synchronicity that I’ve grown to appreciate when I am filming someone working on their craft. But this is altogether different from many other subjects that I’ve documented.

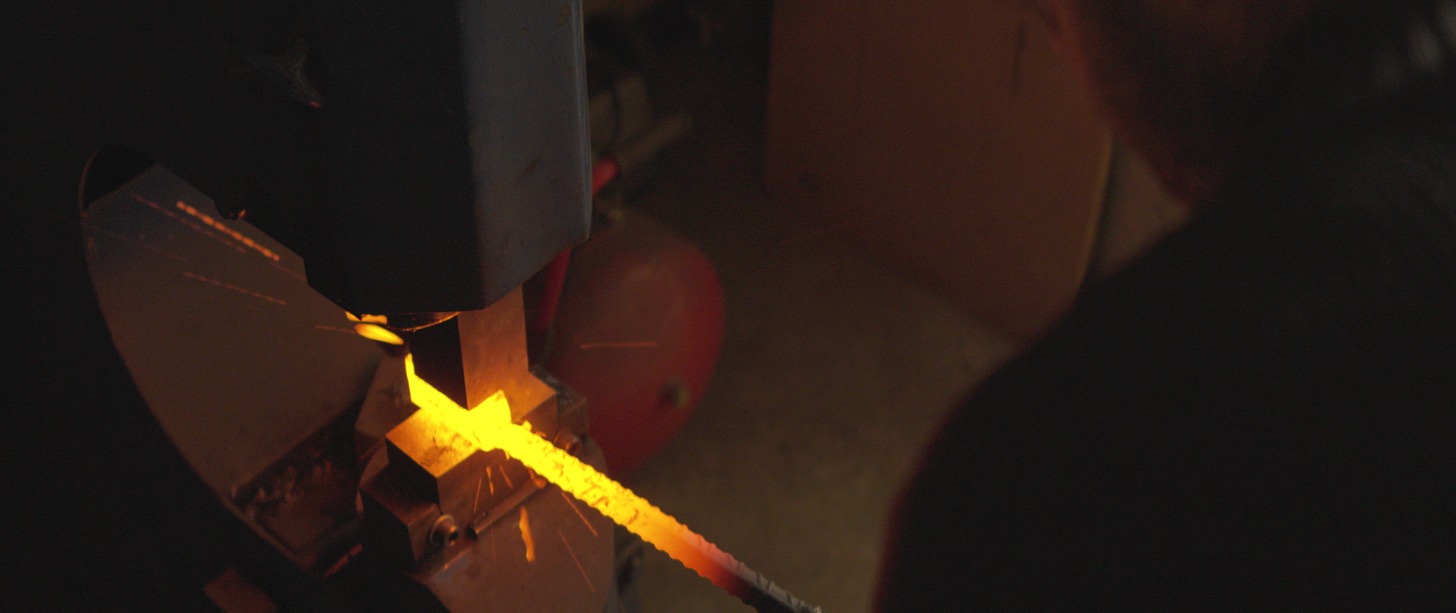

As he begins welding for the first formation of the knife, sparks fly.

He dashes quickly towards the furnace, and I’m learning quickly that with knife-making, timing is everything. So begins a sequence of back-and-forth motions between various machines, the anvil, and back to the furnace again. Cut, crackle, grind, bang.

“You’ll probably need these…” I’m handed a pair of earplugs, and quickly I realise why.

He takes the knife-in-the-making — currently a metal block welded to steel rebar — and brings it with his characteristic speed over to his biggest tool in the workshop. A solid square of metal moves up and down with tremendous force, hitting the piece into a flat and uniform shape.

It feels a little like what I would imagine an industrial revolution-era factory to be. A dark space, illuminated by sparks and flames, reverberating with deep rumbles and strikes. It’s a multi-sensory experience unlike any other.

In between these small windows of hyperfocus, he cracks jokes that remind me of typical British humour — something I wouldn’t have expected from a high alpine farmer.

He reaches into a pot full of white powder, sprinkling the dust onto the knife. “This is the pure cocaine, just like St. Moritz!” he bellows, followed by a deep chuckle.

The setting of the Engadin valley is interesting in a myriad of ways. It’s a pristine alpine landscape that would inspire any artist…if only they could afford to live here.

In the mid-to-late 1800s, Johannes Badrutt brought over his wealthy aristocrat friends from the United Kingdom. He made a bet that St. Moritz would make the ideal location for a luxury ski resort. It would be fair to say that now, a little over a hundred years later, this bet was certainly won.

These streets are paved with gold — but not for you.

Over time, a region that depended mostly on subsistence agriculture was transformed into a hub for luxury tourism. The historically local dialect of this region, Romansh, is scarcely heard on these streets anymore.

Roger tells me that on one side of the valley, the properties are owned exclusively by billionaires. The local airstrip regularly welcomes private jets from global elites on their stopover journeys between the countless holiday homes and estates that they own across the world.

I ask him how it is to live here now as a multi-generational local and see how this region and its unique culture have changed. His answer still lingers in my head: “If they weren’t here, I would have no one to sell my knives to.”

In my interpretation, it speaks to the harsh economic realities that we all face.

Similar to rural Portugal, locals who have lived there for hundreds of years are forced to abandon their homelands for the cities.

This context in the Engadin is essentially the same dynamic, but in reverse. It’s a topic that hurts my brain to consider — how deeply entrenched we all are within the dominant paradigms. Sometimes it’s easier to see the inevitable collapse of our dysfunctional system than it is to see a way out of it.

Yet still, there are cracks in the concrete through which new life emerges.

This is what draws me in, again and again.

I had a conversation with an Irish filmmaker the other day. He asked me if I thought I would find other characters here to film with for Serra as I had done already in Portugal. It was a valid question and one that I had pondered on already.

Let’s see, I told him.

And now, I’m seeing.

You have your answer already - Serra is a Universal reality, feeling; you can go anywhere, there will always be a Serra and People with Stories to Tell.

Hello Adrian. I know you posted this almost a month ago, but I only just read it now.

I read an article a few years back and a quote from it has stuck with me since that seems appropriate here.

"I counted on the permanence of nothing in my life except my ability to meet the challenge of change."

It sounds like there's some changes in your life. I hope this quote brings you some comfort as it did me.

✌️✌️